Update 2/23/15: The Department of Mineral Resources has criticized certain aspects of our story. Our response is here. We also made two changes to this story. We noted that it is possible to request a final spill report from the Department of Mineral Resources in addition to the other ways listed. We also added a comparison of spill rates between 2006 and 2012 to be consistent with the data Lynn Helms used in his 2013 testimony to the North Dakota legislature.

On a muggy day in August, Daryl and Christine Peterson spent hours driving me along gravel roads through farmland damaged by wastewater spills in Bottineau County, North Dakota. Just south of the Canadian border in the central part of the state, Bottineau has been producing oil for decades, but has largely been left out of the state’s most recent boom. Now, rusty pumpjacks and tanks rise above a green quilt of soybeans and wheat.

Daryl Peterson stopped the truck in the middle of a field. In front of us lay a large expanse of bare soil caked with white salt and covered with pools of standing water. One sump pump sat near the edge of the road. In July 2011, a wastewater pipeline here leaked, damaging some 24 acres of land. The pipeline was from a well operated by Petro Harvester, a Texas-based oil company whose focus is aging oil fields.

The oilfield spill problem here has been getting worse for years, but state regulators and inspectors have downplayed how bad it really is — and have made it difficult to fact-check their claims.

Wastewater is particularly damaging to agricultural land. According to North Dakota State University soil scientist Larry Cihacek, the effects can last decades or even generations. The outline of a New Mexico wastewater spill he worked on in the early 1980s is still visible on Google Earth. In 2013, North Dakota produced more than 13 billion gallons of oil and nearly 15 billion gallons of wastewater.

A company must report a spill within 24 hours and fill out an official Environmental Incident report. But these reports are riddled with inaccuracies and estimates. Volumes are often rough estimates, rounded to the nearest 10 or 100 barrels. In about five percent of spill reports submitted to the state since 2006, the volume section of the form was left blank.

In the Petro Harvester spill near the Peterson’s land, the state’s official report says 12,600 gallons spilled. But on the back side a note from a health inspector reads, “Duration and volume really unknown, but very large.” And a notice of violation from the state’s Department of Health to Petro Harvester shows the company later hauled off over 2 million gallons of wastewater, making it one of the largest spills in state history. The official spill estimate was never updated — not in the state’s report, and not in the Department of Health’s database of spills.

Peterson, who is suing some of the companies responsible for spills on his land, believes the underreporting has contributed to the slow pace of clean-up and lack of media coverage of the spill.

“This minimizing is only going to benefit the regulators, who can say spills are down, and the oil companies, at the expense of the landowners and the farmers,” he said.

Inaccurate report volumes don’t appear be a priority for inspectors like Kris Roberts at the Department of Health. In a legal deposition provided to Inside Energy by Peterson’s lawyer, Roberts said, “the volume that was spilled or recovered is not as important as what is done to clean up the problem.”

Lynn Helms, director of the Department of Mineral Resources, said the expectation that spill volumes will be accurately reported initially is “completely misleading.” He said the final spill report does reflect up-to-date numbers, but these are only available years after the incident and are hard to find. To see them, one would either have to pay $50 for an annual subscription to the state’s oil and gas division website or go in person to the Department of Mineral Resources office in Bismarck.

Not only are the accessible reports unreliable, but state officials are, too. On multiple occasions, employees of the state’s Department of Mineral Resources misrepresented the extent of the state’s spill problem in public and in interviews with reporters.

In January 2013, Director Lynn Helms testified in front of the state legislature against a bill to require monitors on all wastewater pipelines, saying the proposal was too broad and that the monitors would not be effective in catching the smallest leaks.

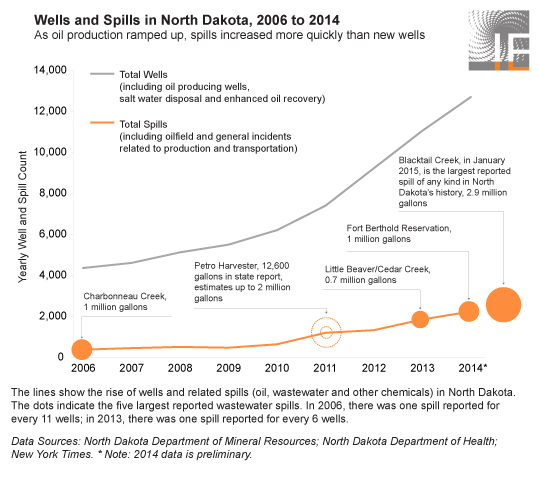

“Yes, the number of spills is up,” he said. “But look at it in comparison to the number of wells. The rate of spills is way, way down.”

In fact, using the state’s own data, we calculated that the rate of spills was way, way, up. It’s more than twice as high as it was in 2006, at the start of the Bakken boom, and three times as high as in 2004.

That wasn’t the only time Helms misrepresented the problem. In August 2014, at a meeting in Antler, North Dakota, for farmers and landowners affected by wastewater spills, Helms told the crowd that the spill rate per well was steady or down. His assistant director, Bruce Hicks, made similar statements in an interview with Inside Energy later that month.

When asked to explain his remarks, Helms said he does not “get into a whole bunch of statistical analysis business” when speaking with farmers or the general public. “The detailed statistics are lost on them or just simply don’t work in making a presentation.”

The detailed statistics are lost on anyone looking for them online, too. The Department of Mineral Resources will, when asked, send along a table summarizing the number of spills per year. But this table does not include spills that happened off of a well-pad — some of the largest and most destructive spills. In September 2013 a Tesoro pipeline break spilled almost a million gallons of oil into a farmer’s field.

Helms defended the department’s approach, saying spills like the Tesoro pipeline are outside his jurisdiction and not a reflection of how well the state’s rules are working. As for not providing data, “the general public is not interested in some kind of detailed spreadsheet analysis of the spills,” he said, “they’re looking for the data journalists to provide that for them.”

That’s fine, said Mark Horvit, the executive director of Investigative Reporters and Editors, as long as the state provides the information in a usable form — which it’s not doing.

“Government officials are perfectly aware that if they give information out in a very difficult to use format, odds are no one will use it and they can completely control the message,” he said. “In too many cases, that is their goal.”

Farmer Daryl Peterson agreed with Helms: He wouldn’t want to dive into a spill database himself. But he would like to be able to find out if the problem is getting worse.

“The future of agriculture in North Dakota depends on it, the future of our quality of life in North Dakota depends on it,” he said. “We can’t be operating on smoke and mirrors.”

It’s important to note that North Dakota’s spill transparency issues are not unique, nor are they the worst we encountered. Neither Wyoming nor Pennsylvania make anything available online — no spill incident reports, no database showing basic information about spills or summary statistics. Even Colorado, whose Oil and Gas Conservation Commission publishes a summary spreadsheet on their homepage with updated information about spills, including the latest spill volume estimates, and annual totals, could stand to improve their transparency. Their comprehensive database is actually harder to search than North Dakota’s.

For Carl Weimer, executive director of the watchdog non-profit Pipeline Safety Trust, being transparent on spills can benefit, not burden, regulators.

“The more information regulators make available,” he said, the more it will “really help rebuild trust in pipeline safety in places where it’s been lost.”

Patience may be wearing thin on spills in North Dakota and with the Department of Mineral Resources’s handling of them. After all, the biggest spill in state history happened last month. In early February, Republican Rich Wardner, Senate Majority Leader, testified in favor of a bill to beef up pipeline monitoring and inspections. He said he’d like an independent inspector to do the job because he didn’t trust the state.

“I’ve just about had it up to my eyeballs with people taking care of their own,” he said. “When you have the fox guarding the henhouse, it’s not very good.”

Helms now says he’s unhappy with North Dakota’s track record on spills, and wants to see spill rates come down. And at a regulatory meeting last month, Governor Jack Dalrymple said he’d like to see stricter construction standards for pipelines near waterways.

Recently, some lawmakers have criticized Helms for being too cozy with the industry, and have proposed amending the state law that requires oil and gas regulators to also promote and encourage oil and gas development. But on Friday, lawmakers overwhelmingly voted that bill down.

What’s Next:

- Browse The New York Times’ searchable database of spills, which they created by scraping data from the North Dakota Department of Health’s website, and read their accompanying stories.

- Read ProPublica’s 2012 report on North Dakota’s spill problem and check out their spills map.

- Check out another colorful map plotting spills in North Dakota by size and type of liquid spilled.

- See how your state fared in the Pipeline Safety Trust’s website transparency review.